Pancreatic cancer is a very difficult disease to cure. It’s projected to be the number two cancer killer in America within this decade.

According to the most up-to-date figures from the American Cancer Society, released in this January (2017-2018 data), it’s already at number three — trailing lung and colorectal cancer.

Pancreatic cancer is rare. It will account for only 3% of cancer diagnoses this year, but it will be implicated in 8% of all cancer deaths. It has the highest mortality rate of all major cancers.

“More than 60,000 people will be diagnosed with pancreatic cancer this year,” said Peter Allen, MD, Chief of the Division of Surgical Oncology at Duke, “and nearly all of them will die from this disease within five years because of late stage at diagnosis and the relative ineffectiveness of current systemic therapies. There is an urgent need for novel strategies to improve patient outcomes for this disease.”

Allen has devoted the better part of the last decade researching ways to move those numbers by nipping this lethal disease in the bud.

He’s currently leading a National Institutes of Health (National Cancer Institute)-funded first-in-human clinical trial aimed at preventing, in high-risk patients, the development of pancreatic adenocarcinoma, the most common type of pancreatic cancer. [Preventing an Incurable Disease: The Prevention of Progression to Pancreatic Cancer Trial (The 3P-C Trial)]

The trial, for which Allen is principal investigator, is multi-institutional. The other sites include Johns Hopkins University, Massachusetts General Hospital and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Allen has long worked with research colleagues at these institutions as part of the Pancreatic Surgery Consortium.

“This trial represents the first of its kind for pancreatic cancer,” said Allen, going on to describe how this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 study will track progression of disease — from a pre-cancerous to a potentially-cancerous state. “Surveillance and/or pancreatic resection is the current clinical practice for pre-cancerous cystic lesions (IPMN) of the pancreas. Patients will be actively surveilled throughout a three-year treatment course of the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug sulindac.”

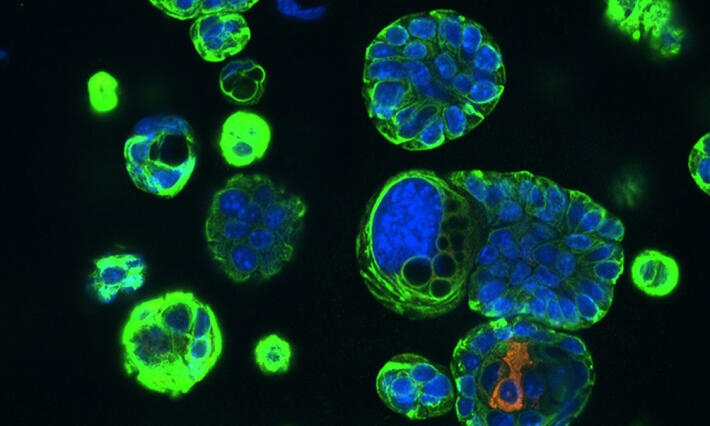

Approximately 10% - 15% of the general population have cystic neoplasms (also called lesions or tumors) in their pancreas. The majority are benign and cause no symptoms. About half of these cysts are the IPMN type that Allen is studying in this trial, short for intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas.

It’s believed that only a minority of these IPMNs progress from their benign low-grade state through to high-grade and invasive carcinoma — an estimated 35 to 40% — but when they do morph into a high-grade, pre-cancerous state, they can cause significant inflammation in and damage to the pancreatic ducts.

Clinical data from Allen and his research colleagues in the Pancreatic Surgery Consortium has shown a strong association between inflammation and cancer progression in patients with high-grade IPMN of the pancreas.

Most pancreatic lesions, including IPMNs, will be found “incidentally” during MRIs or CT scans for non-pancreas-related conditions. They’re being identified more and more often, largely owing to improved detection technologies.

When high-grade IPMNs are discovered, said Allen, this represents the only radiographically identifiable precursor lesion of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. It is these lesions that are often recommended for surgical removal — a partial pancreatectomy — because of their likelihood of turning cancerous and causing even more damage to the pancreas.

“IPMN is a whole-gland process. It’s known that patients who undergo partial pancreatectomy for IPMN have an increased risk of developing cancer in the part of the pancreas that’s left in the body,” Allen explained. “Between our four centers, we were already following more than 450 patients who had undergone resection for IPMN when we designed the trial. Recent data from our group has shown that approximately 25% of these patients will develop radiographic signs of IPMN progression within three to four years of surgery.”

The 3P-C drug sulindac, a COX-2 inhibitor and anti-inflammatory medication, has been shown in a single small observational study to potentially decrease the size of IPMNs in the patients who harbor them. And the drug has proven to be highly effective at preventing a progression to malignancy in pre-clinical (mouse) models. Allen is hoping that sulindac will prevent progression of IPMN in patients enrolled in this study.