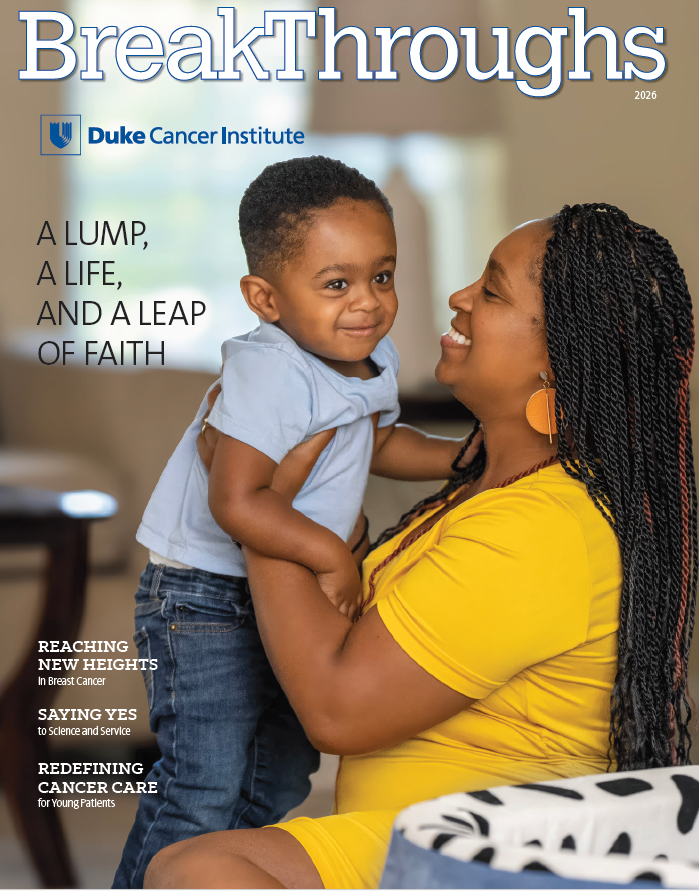

Our Cover Story: A Lump, a Life, and a Leap of Faith

At 18 weeks pregnant, Arlene Brown learned she had triple-negative breast cancer. Within days, she began treatment at Duke Cancer Institute. Today, more than two years later, she’s a proud mom to toddler Andrew — with no signs of recurrence. Photo by Erin Roth.